Maize remains at the center of poultry rations (often constituting about 55–60%) because of its nutritive value and relatively fewer anti-nutritional factors (ANFs) than most energy ingredients; however, newly harvested maize (NM) used within two months can adversely affect growth and gut function due to higher moisture, immature starch, and ANFs (e.g., resistant starch, NSP, phytic acid, protease inhibitors). These risks are amplified where multi-mycotoxin co-contamination is common during/post-monsoon, even when individual toxins are found within permissible limits. This calls for a comprehensive risk assessment while utilizing new maize in poultry rations (Zhong et al., 2019; Guerre, 2020; Palacios-Cabrera et al., 2025).

Maize remains at the center of poultry rations (often constituting about 55–60%) because of its nutritive value and relatively fewer anti-nutritional factors (ANFs) than most energy ingredients; however, newly harvested maize (NM) used within two months can adversely affect growth and gut function due to higher moisture, immature starch, and ANFs (e.g., resistant starch, NSP, phytic acid, protease inhibitors). These risks are amplified where multi-mycotoxin co-contamination is common during/post-monsoon, even when individual toxins are found within permissible limits. This calls for a comprehensive risk assessment while utilizing new maize in poultry rations (Zhong et al., 2019; Guerre, 2020; Palacios-Cabrera et al., 2025).

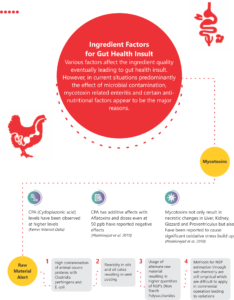

One of the aspects which takes a back seat during the use of newly harvested maize in poultry is the multifactorial gut-health risk associated with new maize. Gut health disturbances can have negative effects on growth performance, compromise gut integrity, and increase nutritional inefficiencies. The areas of concern include the physiological immaturity and comparatively higher moisture levels of new maize. These can heighten anti-nutritional burden and expose birds to higher mycotoxin contamination under warm, humid, post-harvest conditions that are common across South Asia.

This challenge can have a deleterious impact on gut health, impair digestion and absorption, alter intestinal development, and require more intensive nutritional and health management to maintain profitability in operations. For poultry veterinarians and nutritionists, integrating post-harvest controls, mycotoxin surveillance, gut health support, and effective enzyme strategies becomes essential to protect flock performance while incorporating new maize in rations (Zhong et al., 2019; Guerre, 2020; Palacios-Cabrera et al., 2025).

management to maintain profitability in operations. For poultry veterinarians and nutritionists, integrating post-harvest controls, mycotoxin surveillance, gut health support, and effective enzyme strategies becomes essential to protect flock performance while incorporating new maize in rations (Zhong et al., 2019; Guerre, 2020; Palacios-Cabrera et al., 2025).

Qualitative Comparison: Newly Harvested vs. Aged Maize

Controlled trials show clear compositional differences between NM (harvested <2 weeks) and aging maize (AM) (stored ~1 year): moisture 16.05% vs. 13.60%, dry matter 83.95% vs. 86.40%, and gross energy 16.08 vs. 16.63 MJ/kg. The higher moisture dilutes nutrients and is operationally relevant because it predisposes to mold growth and spoilage in storage/transport chains (Zhong et al., 2019).

For broilers (1–42 d), Feed: Gain (F/G) was found to be significantly higher in NM vs. partial NM diets, particularly at 22–42 d and overall. This confirmed a consistent feed-efficiency loss when NM was used at higher levels. In the same experiment, mixing NM with AM (1/3 or 2/3 NC) yielded (better) F/G than all NM diets, indicating a dilution strategy can mitigate performance drag when AM is available (Zhong et al., 2019).

New Maize & Gut Health: A Deeper Dive

Newly harvested maize is particularly vulnerable to mycotoxin contamination due to its high moisture content and the warm, humid conditions often present during and after harvest. These conditions are ideal for the growth of toxigenic fungi such as Aspergillus and Fusarium, which can rapidly colonize the grain and produce mycotoxins like aflatoxins, zearalenone, CPA and T2. In practical terms, this means that poultry feed formulated with new maize—especially during or after the monsoon season— holds the risk of introducing significant levels of mycotoxins into the diet, even before the grain enters long-term storage (Palacios-Cabrera et al., 2025).

Another ignored challenge is multi-mycotoxins contamination. Even when individual toxins are within recommended limits, their combined presence can significantly challenge poultry gut health. This is especially true under post-monsoon conditions in India and post-harvest practices often lead to simultaneous contamination by several mycotoxins. Surveys show that up to three or more mycotoxins (e.g., aflatoxins, trichothecenes, zearalenone and fumonisins) can be detected in a single maize sample, particularly in humid, coastal, or tropical regions (Palacios-Cabrera et al., 2025).

Effect of Mycotoxins on Disruption of Intestinal Barriers

Effect of Mycotoxins on Disruption of Intestinal Barriers

Mycotoxins compromise the gut’s defense system in a predictable order, with the most severe effects on the physical barrier. Majorly mycotoxins Aflatoxins, Ochratoxins (OTA) and DON (A trichothecenes subtype), have been reported to have been reported to exert stronger effects on the intestinal barrier. First, they disrupt the tight junctions between intestinal epithelial cells, leading to increased gut permeability or “leaky gut.” This allows pathogens, toxins, and antigens to cross into the bloodstream, increasing the risk of systemic infections and inflammation. Second, mycotoxins reduce the production and secretion of mucins and antimicrobial peptides, thinning the mucus layer that normally protects the gut lining from direct microbial attack. Third, they dysregulate immune signaling, often increasing pro-inflammatory cytokines while reducing protective antibodies, which impairs the gut’s immune defense and makes birds more susceptible to infections. Finally, mycotoxins alter the gut microbial balance, reducing beneficial bacteria and allowing harmful bacteria to proliferate, which can further worsen gut health and performance (Gao et al., 2020; Guerre, 2020). For poultry stakeholders, this means that gut health programs should address all four barriers, not just focus on pathogen control and a strategy could be mitigation of underlying gut inflammation development.

Effect of Combined Mycotoxins Even Within Recommended Levels

Research consistently shows that when multiple mycotoxins are present—even if each is below its individual regulatory threshold—their combined effects can be additive or even synergistic. This means that the total damage to the gut barrier, immune system, and overall bird health can be much greater than expected from any single toxin alone. For example, birds exposed to both aflatoxins and CPA (Cyclopiazonic acid) at “safe” levels may experience more severe gut barrier breakdown, immune suppression, and dysbiosis than those exposed to just one toxin. This is especially relevant in Indian conditions, where feed ingredients are often contaminated with more than one mycotoxin due to climatic and storage factors. The practical implication is that compliance with individual mycotoxin limits does not guarantee safety—risk assessments and management strategies must consider the total mycotoxin burden and the possibility of interactions (Malekinejad et al., 2011; Gao et al., 2020; Palacios-Cabrera et al., 2025).

Effect of Mycotoxins on Poultry Gut Microbiota

Mycotoxins can significantly disturb the gut microbiota, leading to dysbiosis—a shift in the balance of beneficial and harmful bacteria. Studies in poultry have shown that mycotoxins reduce populations of beneficial bacteria such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, while allowing pathogenic bacteria like E. coli and Clostridium perfringens to proliferate. This disturbance impairs gut barrier function, increases inflammation, and reduces the bird’s ability to resist infections. In Indian climatic conditions, the risk of mycotoxin-induced gut microbiota disturbance is particularly high due to the country’s warm, humid climate, variable post-harvest practices, and reliance on maize and other susceptible grains in poultry feed.

Indian studies and field reports have documented frequent co-contamination of feed with aflatoxins and trichothecenes, especially during and after the monsoon season. This co-occurrence leads to significant shifts in the gut microbiota, with reductions in beneficial lactic acid bacteria and increases in pathogenic bacteria, predisposing flocks to enteric diseases and poor performance (Gowda et al., 2013; Reddy et al., 2020). Furthermore, changes in the microbiota can alter the metabolism of nutrients and even create a vicious cycle of gut health decline.

Effect of Mycotoxins on Gut Inflammation

Mycotoxins are potent triggers of gut inflammation. They cause both acute and chronic inflammatory responses by damaging the gut lining and disrupting immune regulation. Chronic inflammation, often seen with ongoing mycotoxin exposure diverts nutrients away from growth, reduces feed efficiency, and can worsen tissue injury. Mycotoxins like aflatoxins, trichothecenes and CPA have been shown to increase pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β), reduce anti-inflammatory mediators, and impair the gut’s ability to return to a healthy, balanced state. This not only increases disease risk but also impacts flock performance and productivity (Malekinejad et al., 2011, Broom & Kogut, 2018; Guerre, 2020).

For field application, “gut inflammation” develops due to multiple factors in which presence of mycotoxins appears to be one of the core reasons. It comes at the expense of about 0.27 g of ideal protein per bird per day (Sandberg, F. B. et al., 2007; Klasing, K. C., 2007) when measured in simulated models. Translating commercially, the losses could be estimated to be about 60g of feed lost per broiler amounting to almost Rs 2.5 to 3 per broiler bird. Undesired intestinal inflammation weakens gut integrity and aggravates dysbacteriosis, promotes translocation of pathogens from gut into system and importantly puts the gut in oxidative stress further compromising the immune function associated with gut. Eventually, the diversion of nutrients to bring about an inflammatory response reflects in economic losses.

Management and Mitigation: What to Do When We Must Use New Maize

Microbiota & Gut Integrity Support

A strategy is needed to maintain strong protection against Necrotic Enteritis, which remains a major gut-health issue in poultry. Since, new maize could result in gut damage further acting as predisposing factor for NE.

Keeping in mind the inflammatory effects, a strategy to counter gut inflammation simultaneous to microbiota balance is becoming a must to effectively manage poultry gut health and subsequent litter quality.

In this regard a combination strategy of proven Bacillus strains with potent specific anti-inflammatory photoactive could pave a way forward.

Mycotoxin Risk Management

Having a comprehensive mycotoxin screening strategy to assess total burden rather than single-toxin and

Employing a broad-spectrum toxin binder effective against polar and non-polar classes can reduce luminal bioavailability and protect barrier function.

Additionally, mitigating the unseen risk of pesticide residues by using relevant binders could be an effective practice

Post-harvest & Storage Controls

Prefer conditioning/holding new maize > 8 weeks where possible; when not feasible, mix NM with AM (e.g., 1:2 or 2:1) to dilute ANFs and performance penalty suggested by organ-weight and F/G data (Zhong et al., 2019).

Mechanical drying to safe moisture before binning; maintain aeration and hygiene to limit mold growth.

Formulation & Processing

Addressing resistant starch by inclusion of amylase/glucoamylase and xylanase/NSPase and to support duodenal digestion could be a helpful strategy along with considering phytase optimization and Ca/P re-balancing to offset the selective mineral-utilization deficit seen with new maize

Energy matrix & amino acids: Recognizing the lower GE and DM of new maize and adjusting energy and amino acid density accordingly.

Detailed references available upon request

by Dr. Satyam Sharma and Dr. Prateek Shukla, Kemin South Asia